Many of you know that I have been working, seemingly tirelessly, to raise awareness of the Minisry of Justice’s (the MoJ’s) consultation on the ‘Storage and retention of original will documents’. The MoJ proposes to destroy original proabte documents, and potentially other classes of documents, following their digitisation and after holding the originals for a limited number of years. These documents relate to England and Wales and date back to 12th January 1858. The consultation was published by the UK Government on 15th December 2023 and can be viewed online here. On the same day a press release appeared online, as well as a video on the MoJ’s social media accounts, which made no mention of the destruction of the original documents.

There is still a small window available for you to submit your response to the consultation. Anyone anywhere in the world can respond by emailing civil_justice_poli@justice.gov.uk by Friday 23rd February 2024 at 11.59pm (GMT). I would encourage you to do so! You do not need to make reference to the questions in the consultation and can raise your views in any way you feel comfortable.

On 2nd January 2024, I submitted a petition to Parliament which the House of Commons ‘Petitions Communications and Engagement Manager’ edited, stating:

“Before we can accept your petition, we’ll need to make a few changes, to ensure your petition meets our standards.”

You can see both the original wording of the petition and the updated text on my blog post: Justice for Wills and Probate Documents. The petition was publised on 9th January 2024 and currently has 13,966 signatures. It is waiting for a response from the Government and will be considered for debate in Parliament if it reaches 100,000 signatures. To sign the petition follow this link: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/654081

You can continue to make your voices heard, by contating Mike Freer in his role as Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Ministry of Justice, by emailing: correspondence.mc.mikefreer@justice.gov.uk. You can also contact the MoJ by using their online contact form: https://contact-moj.service.justice.gov.uk/.

I have decided to published my response to the MoJ’s consultation, which is found below. Like many of you, I have been plagued by illness since the start of the year, so my response comes fairly late to the many excellent responses which have been published online by both individuals and organisations. It may contain errors, but they are my own and I would welcome any corrections to statments made that may be incorrect.

Finally, in other news, my appeal against The Information Commissioner’s (the IC) Decision Notice continues to go ahead. In May 2023, I had attempted to access a copy of an original will under Freedom of Information. The MoJ explained their view that original wills were not subject to the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The IC made an application to the Tribunal to strike out my case, i.e. bring it to an end. I was invited to respond to the application, and while my response was not given to the Judge when they made their decision, the IC’s application to strike out the case was denied based on the arguments in my grounds of appeal. The MoJ have now been added as a party to the case.

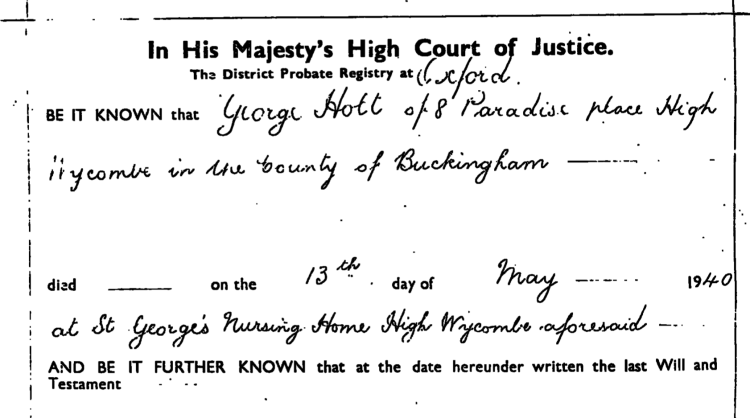

Copy of Grant of Probate for George HOLT (1852-1940)

Response to MoJ:

Dear Ministry of Justice,

RE: Response to ‘Storage and retention of original will documents’

I am an independent researcher and Member of AGRA (the Association of Genealogists and Researchers in Archives). Members of AGRA are experienced professional genealogists who have demonstrated a high level of competence in carrying out paid research. I regularly use probate documents. They are a major source of historical and genealogical information, along with other major sources such as census and [civil] registration records.

Please find my response to the consultation questions below.

Question 1: Should the current law providing for the inspection of wills be preserved?

Yes, the current law should remain, although the procedures for the public inspection of probate documents should be reviewed, which is discussed in my answer to Question 2.

Question 2: Are there any reforms you would suggest to the current law enabling wills to be inspected?

No, I do not suggest any reforms to the law as it stands. However, I would argue that the law is not currently being implemented by the government correctly. One issue that needs to be considered is the mechanism by which access is granted to original wills, rather than office copies. Also, consideration needs to be given to what “open inspection” looks like in practice. Section 124 of the Senior Courts Act 1981 (the SCA) mentions “original wills and other documents”, explaining that “any wills or other documents so deposited shall[…] be open to public inspection.” This includes all related probate documents, not only the will and grant of probate. Currently, it is only possible to obtain a copy of the office copy via the Probate Search Service, unless the will was proved from 2021 onwards, in which case a copy of the original will is provided.

The current practice may be due to the wording of Section 125 of the SCA, which only mentions “an office copy, or a sealed and certified copy, of any will[…] may, on payment of the fee[…] be obtained [from the place of deposit].” This section makes no provision for the inspection of “original wills and other documents” as discussed in Section 124 of the SCA.

Formerly, the Public Records Act 1958 (the PRA) contained legislation relating to probate records in Section 8(2), which was repealed by the SCA, Section 152(4), Schedule 7. The wording of Section 8(2) of the PRA meant that probate documents fell under Section 5(5) of the said Act, whereby:

“The Secretary of State [formerly the Lord Chancellor] shall, as respects all public records in places of deposit appointed by him under this Act outside the Public Record Office, require arrangements to be made for their inspection by the public comparable to those made for public records in the Public Record Office.”

It is not certain how the repeal of Section 8(2) of the PRA affected the provisions of Section 5(5) of the said Act in respect to probate documents. However, I believe the same provisions in Section 5(5) of the PRA should have been maintained. Section 8(2) of the PRA was repealed due to the fact that the same provisions were made under alternative legislation, namely the SCA. The SCA included the right to “open inspection” of the records, which, in my view, was likely intended to replicate the provisions under the PRA, specifically Section 5(5).

When the Courts of Probate Act 1857 was enacted, copies of original wills and letters of administration, known as office copies, were formerly sent to the Principal Registry for public inspection. The original wills and other documents were deposited at the District Registries where the registrars had to make provisions for their inspection. Unfortunately, the same provision of public access to wills and other documents, while it remains in law, does not remain in practice. This needs to change!

Question 3: Are there any reasons why the High Court should store original paper will documents on a permanent basis, as opposed to just retaining a digitised copy of that material?

Yes. There are many reasons why the original documents should be kept on a permanent basis. My top two reasons are mentioned below, although this is by no means an exhaustive list. I am aware of many other reasons which have been provided in response to the consultation by organisations and individuals who work in the same, or similar field, to myself.

1. No digitisation project is without error. It is inevitable that every digitisation project will fail to capture at least some of the information in the original documents. From my own experience, the Probate Search Service has already failed to accurately digitise all of the information contained in documents. For example, I was provided with a copy of a will that was proved in 2022 which started mid-sentence and was missing a page. The original needed to be retrieved and rescanned. If the Ministry of Justice destroys the original documents, information that was not captured by digitisation would be lost forever.

2. Digitisation is not a relevant response to reducing the storage costs of the probate archive. Digitisation projects are expensive and such a project will ultimately fail unless it is combined with a thorough plan that includes digital preservation. Digitisation and digital preservation are not the same thing. The costs for ensuring the perpetual storage of digitised copies of probate documents are not known, nor can they be adequately planned for. We do not know what the future holds in terms of technological advancements. It is also not possible to say that documents digitised today will be readable in centuries time. The claim made by Iron Mountain’s Team Lead in the Ministry of Justice’s video, that “once the [probate documents] are digitised[…] the [digital] files [are preserved] forever and[…] will stay available for centuries” is simply unable to be made. The statement contradicts itself as ‘for centuries’ is not ‘forever’. There has not been an adequate test period of ‘for centuries’ to even begin to contemplate if this statement is correct. What we do know from other such digital libraries, is that they have not stood the test of being available ‘for centuries’. Some have not survived for decades.

Question 4: Do you agree that after a certain time original paper documents (from 1858 onwards) may be destroyed (other than for famous individuals)? Are there any alternatives, involving the public or private sector, you can suggest to their being destroyed?

No, I do not agree that the original documents should be destroyed after any length of time. The probate archive of original documents should be preserved forever. This is the case with all probate documents proved before 12th January 1858. The consultation severely misunderstands or misrepresents the vast collection of probate documents that are held in archives from the 13th century to the 11th January 1858. If the proposals were to go ahead, what precedent does this set for the destruction of these documents, or indeed any other collection of documents? These probate records should all be preserved as a major source of our history and cultural heritage.

The status of probate documents is such that they are public records under the PRA. Under Schedule 1(2)(a) and (b), “records of, or held in, any department of [His] Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, or records of any office, commission or other body or establishment whatsoever under [His] Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, shall be public records.” I believe the original records should be kept in the public sector under their status as public documents in accordance with the PRA, as is currently the case.

Question 5: Do you agree that there is equivalence between paper and digital copies of wills so that the ECA 2000 can be used?

There is no equivalence between original paper documents and digital copies of those documents. Under Section 8(3) of the Electronic Communications Act 2000 (the ECA), an order to modify the legislation surrounding probate documents should only be made where the electronic version or storage “will be no less satisfactory… than in other cases” i.e. storing and preserving the physical documents.

I do not believe that this test, as outlined in the ECA, will be met. This is primarily because digitisation projects are subject to error, with the originals needed to rectify such errors. This is also because an order under the ECA to digitise the probate archive, would be unable to replicate matters of materiality, i.e. the paper, ink and seals present in the original documents. While digital images allow wider access to records, they are not a replacement for the original documents themselves.

Question 6: Are there any other matters directly related to the retention of digital or paper wills that are not covered by the proposed exercise of the powers in the ECA 2000 that you consider are necessary?

Yes, the Ministry of Justice should follow the guidance, policies and procedures that are in place in regard to their legal obligations under the PRA. There is no evidence this has been done or even contemplated in the consultation document itself. Not only does it misrepresent the collections from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury held at The National Archives, it includes The National Archives in the list of organisations that were sent the consultation paper. The paragraph following this list explains: “this list is not meant to be exhaustive or exclusive and responses are welcomed from anyone with an interest in or views on the subject covered by this paper.” This statement has led the public to believe that The National Archives have been asked to comment on or respond to the consultation, however it is my understanding that one government agency cannot comment on nor respond to the consultation document of another government agency. If this is true, it begs the question as to why the Ministry of Justice included The National Archives in this list!

Referring back to the guidance for government departments issued by The National Archives, the guidance states:

“Where departments choose to digitise records, for whatever reason, both the original record and the digitised version are public records…”

It goes on to say:

“Before embarking on any digitisation project, The National Archives (TNA) would recommend that plans are shared with The Advisory Council on National Records and Archives (ACNRA), to help the Departmental Records Officer (DRO) ensure independent oversight and that all relevant guidance is followed. This is particularly important if:

* digitisation is likely to cause damage to the original physical record;

* the intention is to destroy original records that were selected for transfer to TNA [or otherwise permanent preservation];

* the benefits to the public purse of digitising records with either very high or very low selection rates are unclear; or

* the outcome of the digitisation project does not help develop ways of the department using AI in selection techniques.”

As far as I am aware, the consultation indicates no engagement with The Advisory Council on National Records and Archives (ACNRA). This is despite the fact that the Ministry of Justice claims, in the video released on 15th December 2023, that Iron Mountain are “actually in the process of digitising everything right now.” With the Team Lead explaining: “…we estimate that it will take roughly between 15 to 20 years to digitise everything we have in the building.”

This is contrary to the letter issued by Mike Freer, Justice Minister, on 22nd January 2024 [MoJ ref: MC111404] wherein it is stated: “…no decisions on any of these matters [in the consultation] have been made as yet…” This same statement was repeated by Alex Chalk, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice in his letter of 20th February 2024 [MoJ ref: MC112154]. Which statement is correct? Is it the one contained in the MoJ’s video released on 15th December 2023, or in the letters of 22nd January and 20th February, respectively?

Question 7: If the Government pursues preserving permanently only a digital copy of a will document, should it seek to reform the primary legislation by introducing a Bill or do so under the ECA 2000?

I do not agree with the proposal to permanently preserve digital only copies of probate documents. I have already made it clear under Question 5, that due to the wording of Section 8(3) of the ECA, it will not be possible to use this legislation.

Question 8: If the Government moves to digital only copies of original will documents, what do you think the retention period for the original paper wills should be? Please give reasons and state what you believe the minimum retention period should be and whether you consider the Government’s suggestion of 25 years to be reasonable.

I do not believe it reasonable to destroy the original probate documents under any circumstances.

Question 9: Do you agree with the principle that wills of famous people should be preserved in the original paper form for historic interest?

Yes, but this should not be exclusive to the ‘wills of famous people’. This is due to my belief that the probate documents of everyone should be preserved in their original format. I also note that the term “famous people” is not defined in the consultation document, so answers to this question are only based on an individual’s own interpretation of this term. As responses are based on individual interpretations, answers to this question cannot be measured in any way. How one person interprets “famous people” is different to how another person interprets this. Any data generated from responses to this question therefore cannot be used, as the data will have no meaning.

Question 10: Do you have any initial suggestions on the criteria which should be adopted for identifying famous/historic figures whose original paper will document should be preserved permanently?

I do not agree with this proposal.

As mentioned under Question 9, in regard to interpretation of the term “famous people”, any data generated from responses to this question will have no meaning.

Question 11: Do you agree that the Probate Registries should only permanently retain wills and codicils from the documents submitted in support of a probate application? Please explain, if setting out the case for retention of any other documents.

It is my view that the documents listed under paragraph 53 are all worthy of permanent preservation in their original form. It is also my view that any and all related probate documents are worthy of permanent presentation and that no documents should be destroyed after 50 years have passed. I have been informed by an expert on Irish genealogical research, that the practice in Ireland and Northern Ireland is to not destroy any probate documents from the ‘probate packet’. All such related original documents are kept indefinitely under a precedent that was created by legislation passed in Westminster.

Signed: Richard Holt

One thought on “Response to the Ministry of Justice’s Consultation”